Willem De Kooning Biography (1904-1997)

Childhood And Education 1904-1925

Born in Rotterdam, Netherlands on April 24, 1904, Willem de Kooning is considered one of the world’s foremost Abstract Expressionist painters. His parents, Leendert de Kooning and Cornelia Nobel de Kooning, were both involved in the liquor industry, and Willem grew up in a household which would today be referred to as dysfunctional.

Cornelia gave birth to three other girls, twins in 1901 and another daughter in 1902. None of them survived their first year. Willem was raised with his older sister, Marie, and his step brother, Jacobus Johannes Lassooy (“Koos”), all of whom suffered physical and verbal abuse at the hands of their tyrannical mother, who treated them as she did the rowdy sailors who frequented the bar she owned and operated on the Rotterdam waterfront.

Group portrait, painting studio of Jaap Gidding in the Aert van Nesstraat, Willem de Kooning sitting center front (ca. 1916 – 1920), Photography, inv. 4100, Stadsarchief Rotterdam

Willem's parents divorced when he was five, and the courts awarded custody of the boy to his father, while Marie stayed with her mother. After a short period, his mother kidnapped him and eventually won full custody after two court battles. Willem spent the next seven years with his mother and Marie, with whom he was very close, and eventually with his stepbrother.

At the age of 12, Willem left school and began an apprenticeship with Jan and Jaap Giding, the owners of a large commercial art firm. The Gidings helped him enroll in evening classes at the Academie voor Beeldende Kunsten en Technische Wetenschappen, where he eventually graduated from with certifications in both art and carpentry. His art was strongly influenced by Walt Whitman, Piet Mondrian, Theo Van Doesburg, and Frank Lloyd Wright. de Kooning furthered his studies at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels and at the Van Schelling Design School in Antwerp before leaving for the United States.

The Artist Comes to America (1926-1943)

Willem de Kooning made his way to the United States as a stowaway aboard the SS Shelly, arriving in Newport News, Virginia in 1926. He boarded another ship to Boston, Massachusetts and then a train to Rhode Island, finally settling in Hoboken, New Jersey. Although he spoke little English, he quickly secured work as a house painter, making $9.00 a day.

Within a short time, de Kooning moved to the art mecca of New York City, where he became acquainted with numerous artists and critics, working as a commercial artist and doing side jobs which included carpentry, house painting, window dressing, and painting signs. His acquaintances included Edward Derby, Stuart Davis, and Arshile Gorky, the latter of which became one of de Kooning’s closest and most influential friends.

de Kooning’s interests included a passion for jazz, and in 1929, his employer, A.S. Beck, advanced him the equivalent of nearly half a year’s salary to purchase a Capehart hi-fi sound system. He frequented George’s in the Village, a small diner where he enjoyed jazz and nickel-a-glass beer with fellow artists. de Kooning was also fascinated by Harlem, and David Margolis would sometimes take him to the Savoy Ballroom on Lenox Avenue to listen to jazz and watch the patrons dance.

It was in the late 1920s that de Kooning met Virginia “Nini” Diaz, a tightrope walker on the vaudeville circuit. Both were tenants of a boarding house on West 49th Street, but they soon moved into an apartment together at 64 West 46th Street, at which time, Diaz took his last name for appearance’s sake. They spent the summer of 1930 at the Smith House in Woodstock before relocating to an apartment at 348 East 55th Street. Diaz’s mother came to live with them, and during this time, Diaz had three pregnancies by de Kooning, all of which were aborted.

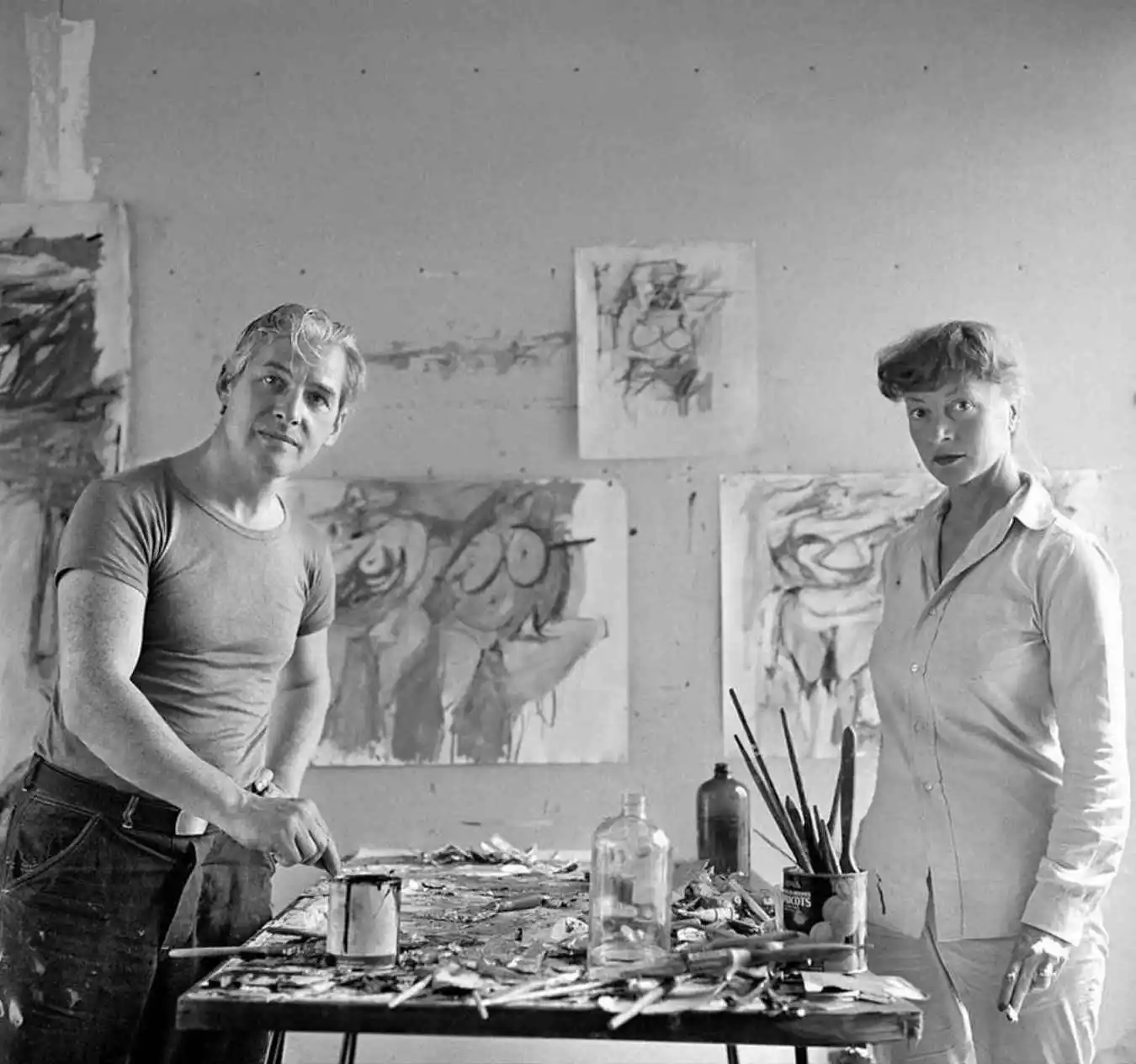

Elaine and Willem de Kooning, undated photo.

de Kooning held numerous parties at his apartment, and it was at such a party in 1934 that he met artists’ model Juliet Browner, a Bronx native who was living in the Village. Diaz was away at the time, and de Kooning and Browner began a relationship, which they disclosed to Diaz upon her return. Diaz moved out, but accepted de Kooning’s invitation to join them at Woodstock later that year. The three continued a ménage à trois, living in a home rented by de Kooning. They were joined there by Marie Marchowsky and her friend, also at de Kooning’s invitation. In August, de Kooning returned to New York while the girls remained in Woodstock.

de Kooning resided at 40 Union Square, owned by architect Mac Vogel, for only a short time before moving to 145 West 21st Street with Browner, who had returned from Woodstock. In early 1935, they met neighbors Rudy Burckhardt and Edwin Denby, who became de Kooning’s fans and the first collectors of his art.

Although Diaz had remained in Woodstock, de Kooning had kept in contact with her. So when his mother came to visit him and his “wife” (his previous correspondence had given the impression that they two were married), he rented a separate apartment and had Diaz come to live with him and play the role. His mother, however, discovered the truth, including the three abortions – facts which added to the strain of the already less than ideal relationship. She was not aware that during this time Diaz again became pregnant and underwent another abortion. This last procedure left her unable to conceive again.

In 1935, de Kooning became a full time employee of the Works Progress Administration Federal Art Project, working under director Burgoyne Diller as a commercial artist in the mural division. This inspired him to make the pivotal decision to devote his life to art, even if it meant menial wages.

While affiliated with the WPA project, de Kooning met art critic Harold Rosenberg, who became the National Arts Director of the WPA’s American Guide Series in 1938. A friendship developed, and Rosenberg visited de Kooning’s studio regularly.

In 1936, de Kooning and Browner moved into a commercial loft at 156 West 22nd Street. His closest friends were Raphael Soyer and Arshile Gorky, who were involved in the newly formed American Abstract Artist group. de Kooning did not want to be a part of the group, however, choosing to change his style frequently in an act of defiance against any constraint of his art.

Just as Arshile Gorky completed his painting of de Kooning, Portrait of Master Bill, in 1936, de Kooning was gaining recognition in the art world. The 1937 release of John Graham’s book, System and Dialectics of Art, named him one of eight “outstanding” painters. In August 1937, he resigned from the WPA, due to the requirement that all their employees must be American citizens.

From late 1937 to early 1939, de Kooning worked on a mural in the Hall of Pharmacy for the World’s Fair, which he called Medicine. Thousands of motorists would be able to see the curved wall of the building decorated with de Kooning’s mural.During this period, he also painted a series of male figures, including Two Men Standing, A Man, and Seated Figure and the abstractions Pink Landscape and Elegy.

In the summer of 1938, Browner moved in with Diaz, while de Kooning lived in the loft alone for a short while. In the fall, he met Elaine Marie Fried, the former girlfriend of Robert Jonas, who worked with de Kooning at A.S. Beck. Fried had developed an interest in the artist based on praise from Jonas and her own art instructor. She was introduced to de Kooning at his studio by a mutual friend, and the attraction was both immediate and mutual. Within a year, the two were engaged to be wed.

Presentation of the Talens Prize to Willem de Kooning (1968), Photography, inv. 921-6911, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

His last old style academic painting was a portrait of Elaine and was produced in 1940-1941. de Kooning found this work tedious, due to his obsessive reworking of the painting and thereafter pursued other techniques. In 1943, he and Fried moved to 156 West 22nd Street, and on December 9, they were married in a small ceremony. Soon after, de Kooning discovered Fried in bed with her ex-boyfriend, Robert Jonas.

Abstract Expressionist Work Takes Shape, 1944-1948

In 1944, the Cincinnati Art Museum featured Willem de Kooning in the Abstract and Surrealist Art in the United States exhibit held from February 8 – March 12. The show later traveled to the Denver Art Museum (March 26 – April 23), Seattle Art Museum (May 7 – June 10), the Santa Barbara Museum of Art (June – July), and the San Francisco Museum of Art (July). After closing, the exhibition moved to the Mortimer Brandt Friends in New York, arranged by Sidney Janis. In 1944, Janis’ book, by the same title, was published.

In January 1945, de Kooning’s painting, The Netherlands, won a competition sponsored by the Container Corporation of America. That autumn, Elaine de Kooning sailed to Provincetown, MA with physician and friend Bill Hardy. de Kooning was less than pleased with this, but his work at the time includes colorful, biomorphic forms, such as Pink Angels.

That year, de Kooning’s painting, The Wave, was shown in the Autumn Salon at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Centuryexhibition. By the mid 1940s, however, he was experiencing economic challenges, exhibiting in only a handful of shows, and his paintings were being purchased almost exclusively by a small circle of friends who patronized his work. Elaine was also struggling, writing ballet reviews for the New York Herald Tribune and painting. One of her pieces, a self-portrait, was sold to her sister for $20.

At this time, de Kooning declared existentialism to be “in the air” but stated that his work would be the same whether or not this was the case. In the spring of 1946, Marie Marchowsky commissioned de Kooning to create a backdrop based on his recent painting, Judgment Day, for her dance performance, Labyrinth, in the New York Times Hall. He collaborated with Milton Resnick using cooked fish glue and cheap hardware pigments for materials.

Presentation of the Talens Prize to Willem de Kooning (1968), Photography, inv. 921-6914, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

By April, de Kooning had become extremely depressed. When Marchowsky threw him a birthday celebration, he arrived in ragged, paint-splattered clothing, looking homeless and sitting in a corner nursing a drink. By late summer, things began to improve, and he rented a storefront studio at 85 4th Avenue, between 10th and 11th Street.

His marriage was still rocky, and de Kooning began spending increasing amounts of time in his studio, only occasionally retiring to his apartment at night. Elaine was absorbed in her own pursuits, and his sole emotional support came from friends, many of whom lived near the studio. Among his friends were Franz Kline, Milton Resnick, Hans Hofmann, John Ferren, and Conrad Marca-Relli.

In November 1946, de Kooning wrote to his father saying that he wanted to see him and explaining that he was happily married and satisfied with his life as a struggling artist. His father’s reply included encouragement to find more lucrative employment.

In 1946, de Kooning assisted Charles Egan in opening an art Friends on 63 East 57th Street, and on April 12, 1948, Egan gave de Kooning his first one-man show. The exhibition consisted of the black-and-white compositions and included the aforementioned paintings. Extended, due to lack of attendance in its opening days, the show eventually drew a good crowd, primarily of young artists. Painting sold to the Museum of Modern Art for $700, but it was the only sale. Nevertheless, critics responded favorably to the show.

In October 1947, Willem de Kooning produced a black-and-white painting for the premier issue of Tiger’s Eye. The magazine editors, John and Ruth Stephan, insisted upon entitling it Orestes, a name Elaine found inappropriate as de Kooning and his art were not associated with Greek mythology. He did, however, continue to paint black-and-white abstracts throughout 1947 and 1948, the medium being a boon as it eliminated the expense of purchasing colors. Many critics consider these paintings, which include Painting, Village Square, and Dark Pond, to be his greatest works.

de Kooning took a summer job teaching at Black Mountain College in North Carolina in 1948. Elaine accompanied him taking classes there. Here, de Kooning began work on Asheville, which he finished after returning to New York in the fall after giving the position to Franz Kline, as Kline needed the income. While de Kooning was at Black Mountain College, his close friend, Arshile Gorky, hung himself at the age of 44.

The October 11, 1948 issue of Life magazine featured an article more than 16 pages long called “A Life Round Table on Modern Art”, wherein fifteen critics and connoisseurs discussed the discipline. As the article referred to “five young extremists”, de Kooning and his works, Painting, Village Square, and Dark Pond, were highlighted.

Near the end of 1948, Willem and Elaine separated, and shortly thereafter, he met Mary Abbott and began an intermittent affair with her, which lasted for several years. During this time, he painted Woman I.

Prolific Years: Exhibitions and Alcoholism, 1949-1967

Franz Kline brought a Bell-Opticon projector to de Kooning’s studio at 85 Fourth Avenue in 1949, and it was then that he almost instantaneously converted to abstraction as he was able to project his small sketches onto large canvases. These large works would become his forte.

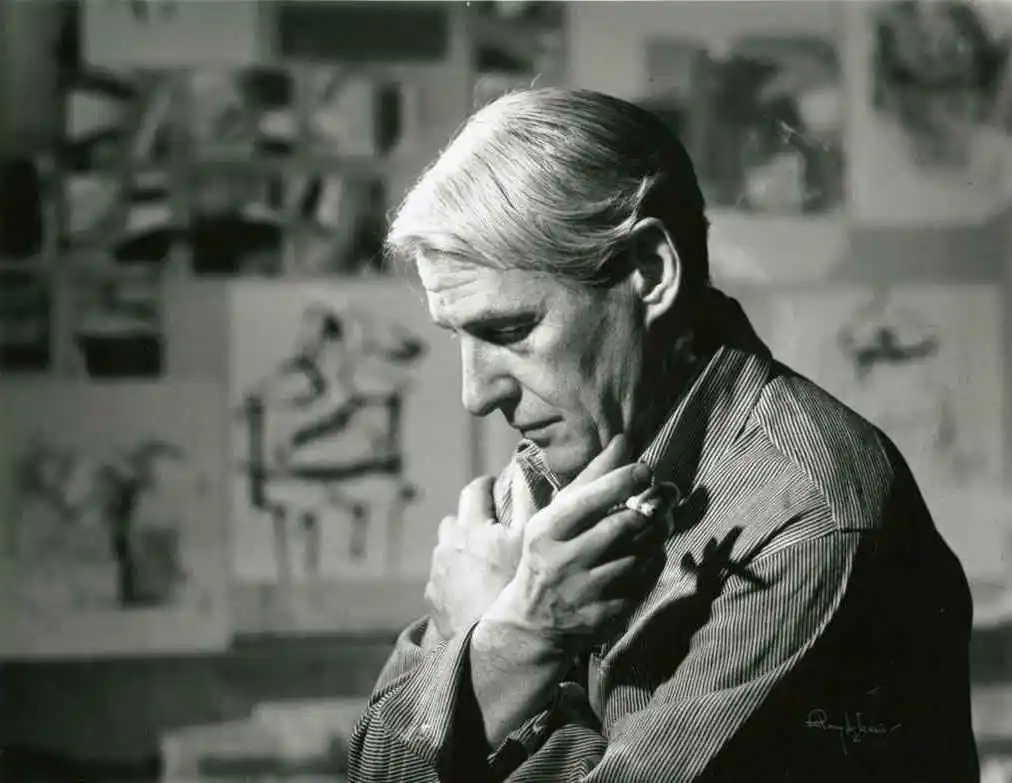

Undated photo of Willem de Kooning in his studio.

Willem and Elaine reconciled and in July rented a cottage in Provincetown. Despite heavy alcohol consumption, he painted Sailcloth and Two Women on a Wharf that summer. In the autumn o 1949, the Sidney Janis Friends held an exhibition called Artists: Man and Wife, which included a portrait of Willem and Elaine. de Kooning was also featured in The Intrasubjectives exhibition, held at the Samuel M. Kootz Friends from September 4 – October 3, 1949.

Due to increasing hostility from the Waldorf Cafeteria, their favorite meeting spot, de Kooning and his artist friends decided to open their own restaurant. The Club, which was located at 39 East 8th Street. It was the product of Giorgio Cavallon, Peter Grippe, Franz Kline, Landes Lewitin, Conrad Marca-Reilli, Phillip Pavia, Milton Resnick, Ad Reinhardt, James Rosati, Ludwig Sander, Joop Sanders, Jack Tworkov, Charles Egan, Mercedes Matter, and Elaine and Willem de Kooning. The artists transformed the space during September. The kitchen was cleaned, a record player and speakers were installed, and secondhand furniture was added. According to Joop Sanders, “We had sort of comfortable furniture for awhile” before Milton Resnick threw it away because it was “too bourgeois.”

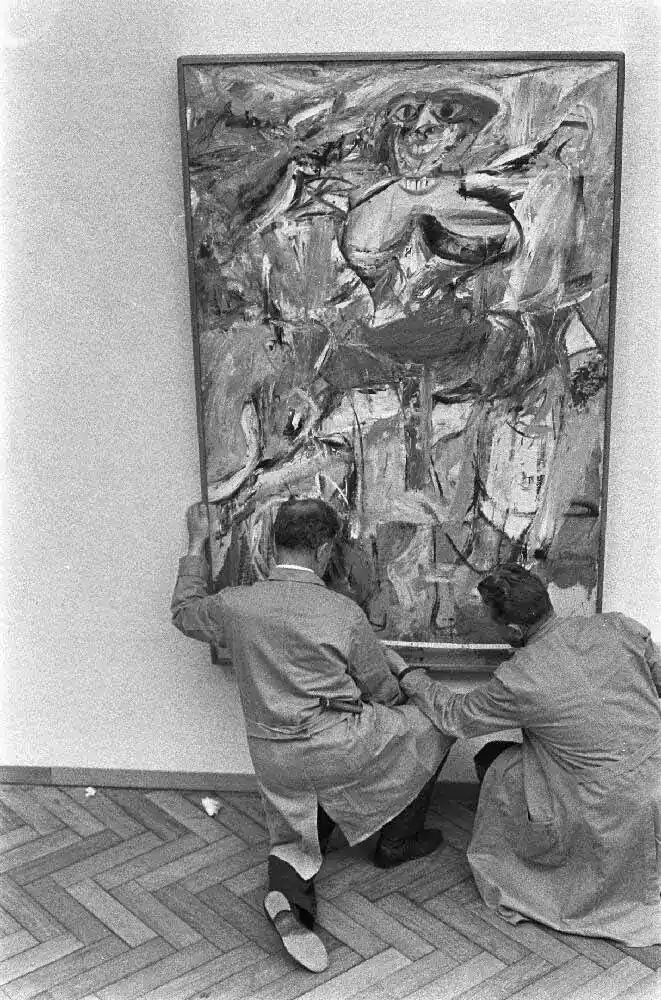

de Kooning began painting his “Woman” compositions in 1950, which proved to be a major year for the artist. Excavation was painted in the spring, and in June, he began Woman I, possibly his most famous work. Although this was not his first Woman picture, having done a similar piece in 1944 and one in 1948, this painting was unique due to its enormity, standing nearly seven feet. Additionally, the portrayal was disturbing to most viewers, and de Kooning remarked that he was painting the irritation he often felt toward women, as opposed to their beauty.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s selection jury was notoriously hostile toward the artists of the abstract movement, so Robert Motherwell and Ad Reinhardt at Studio 35 attempted to form a group, calling themselves Abstract-Expressionist, Abstract-Symbolist, or Abstract-Objectionist. Ultimately the naming of a group was rejected in favor of writing a letter to The New York Times, in which the artists publicly objected to the national jury of selection. The group, supported by Jackson Pollock, picketed the museum and refused to submit art. The New York Herald Tribune called the group “The Irascible Eighteen,” attacking them for distorting facts. The protest received coverage from Time, Life, Art Digest, Art News, The Nation, and other magazines, and on November 26, Life magazine photographed the group, including Pollock who came from Manhattan for the shoot.

de Kooning was one of six artists chosen by Alfred Barr in 1950 to participate in an exhibition of young American painters in the U.S. Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Meanwhile, Sidney Janis Friends held an exhibition called Young Painters in the U.S. and France. The exhibition, which Janis worked on with Leo Castelli, paired American artists with French ones. de Kooning’s Woman(1949-50) was paired with Jean Dude Kooning’s L’Homme au chapeau bleu (1950).

In 1951, Excavation was exhibited in Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America in the Museum of Modern Art from January 23 – March 25. The show was categorized as “pure geometric,” “naturalist geometric,” and “expressionist biomorphic.” In February, de Kooning appeared at a symposium organized by the Museum of Modern Art, explaining his interpretation of abstract art.

In April 1951, de Kooning enjoyed another one-man show, again at the Egan Friends. The earnings were disappointing, however, as the limited sales (three drawings and two paintings) went to absorb the expenses of the exhibition. Despite increased publicity and acclaim, this was a financially poor year for de Kooning. Charles Egan had married Betsy Duhrssen in 1948, while having an affair with Elaine; and in 1950, Durhssen’s mother purchased Light in August for $750 from Egan’s Friends as a gift for the couple. These proceeds were also absorbed, and de Kooning received no money from the sale.

That year, the historic artist-organized Ninth Street Show was held at 60 East 9th Street, including the work of Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, Hans Hofmann, and James Brooks, along with de Kooning’s Woman. Sidney Janis began supporting de Kooning financially in the spring of 1951, advancing him money for art supplies on the condition that he change the name of his studio to the Janis Friends. The name change became official in 1953.

Excavation won a $4,000 first prize in the 60th Annual American Exhibition: Paint and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago in the autumn of 1951. de Kooning was one of 20 artists chosen for the American Vanguard Art for Paris Exhibition at the Sidney Janis Friends December 26, 1951 – January 5, 1952.

After much effort in January and February of 1952, de Kooning ceased work on Woman I, giving up on it until art historian and friend, Meyer Schapiro, encouraged him to revisit it in June. He renewed his efforts and pronounced it finished in mid-June 1952, only to begin more revisions in December. During this time, he also created several new “Woman” pictures.

Although Willem and Elaine were technically separated, he living in his studio and she in an apartment on Carmine Street, Elaine accompanied him to the Hamptons in the summer of 1952. They stayed with Leo Castelli and Ileana Sonnabend at their home on Jericho Road. Regular visitors were art critic Harold Rosenberg, who lived nearby, and Jackson Pollock.

de Kooning moved to 88 East 10th Street in the autumn of 1952, spending much of his time with Harold Rosenberg. He met Joan Ward, a student at the Arts Students League, who was living in the Artists’ Building on 10th Street. Ward had a fondness for de Kooning and spent increasing amounts of time at his studio, sharing his whiskey and eventually becoming pregnant with his child. The pregnancy was aborted.

In 1953, de Kooning officially changed the name of his studio to the Janis Friends. His first show at the Sidney Janis Friends opened in March 1953. A small retrospective of his work was held at the Workshop Center for the Arts in Washington and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

In 1953, art student, Robert Rauschenberg, undertook an artistic experiment in which he, over a period of three weeks, erased one of de Kooning’s drawings with his permission. Under the impression that it was a private experiment, de Kooning was enraged to learn it was exhibited as Erased de Kooning.

Still, he was able to participate in Venice Biennale with Excavation in 1954, which propelled him into fame as a leading Abstract Expressionism artist. That summer he rented a Victorian house in Bridgehampton with Elaine, which they shared with Nancy Ward, Ludwig Sander, and Franz Kline. Although the troop was reportedly quite poor, they managed as steady supply of alcohol and attracted many visitors. de Kooning was able to make some sales to Martha Jackson and used the money for fare for his mother to visit. Her criticism was constant, and their verbal attacks led to her staying at the home of Martha Bourdrez, a Dutch artist and friend of de Kooning. During this time, de Kooning began to paint abstract urban landscapes, working in bright colors that he referred to as “circus colors”.

In 1955, Joan Ward became pregnant with de Kooning’s baby, and on January 29, 1956, she gave birth to Johanna Lisbeth de Kooning. On April 3, his second one-man show at the Sidney Janis Friends was held, and this one was a complete sell-out.

de Kooning was staying with Ward and their daughter at Martha’s Vineyard when Pollock and Edith Metzger died in a car crash on August 11, 1956. Elaine returned from Europe two days later and joined them for the funeral.

In the autumn of 1957, de Kooning began an affair with Jackson Pollock’s former lover, Ruth Kligman, who had survived the crash that killed Pollock and Metzger. Later that year, de Kooning also indulged in a two-week liaison with actress Shirley Stoler, allegedly offering her a painting, which she declined. He was painting very little during this time.

In February of 1958, de Kooning took Ruth Kligman to Cuba to visit Ernest Hemingway’s house. Joan Ward, the mother of de Kooning’s daughter, was furious that he left without notice. Kligman and de Kooning drifted apart that spring, but reconciled in the summer and were together in Martha’s Vineyard. Here, de Kooning became acquainted with lawyer, Lee Eastman.

de Kooning moved his studio to 831 Broadway in early 1959, a large space with windows and a skylight. Thomas B. Hess wrote a monograph on Willem de Kooning, which was published by Braziller in New York. Sidney Janis Friends held a May 4 exhibition of the large abstractions de Kooning was currently producing, a sell-out which included 22 oils bringing from $2,200 for a small piece to $14,000 for five large paintings.

The New American Painting as Shown in Eight European Countries 1958-1959 exhibition, held May 28-September 8 at the Museum of Modern Art, showed de Kooning’s Woman series, as well as some of his urban landscapes. On June 23, he bought 4.2 acres of land located on Woodbine Road, just off the main highway to East Hampton in the Springs of Long Island. The price was $500 an acre.

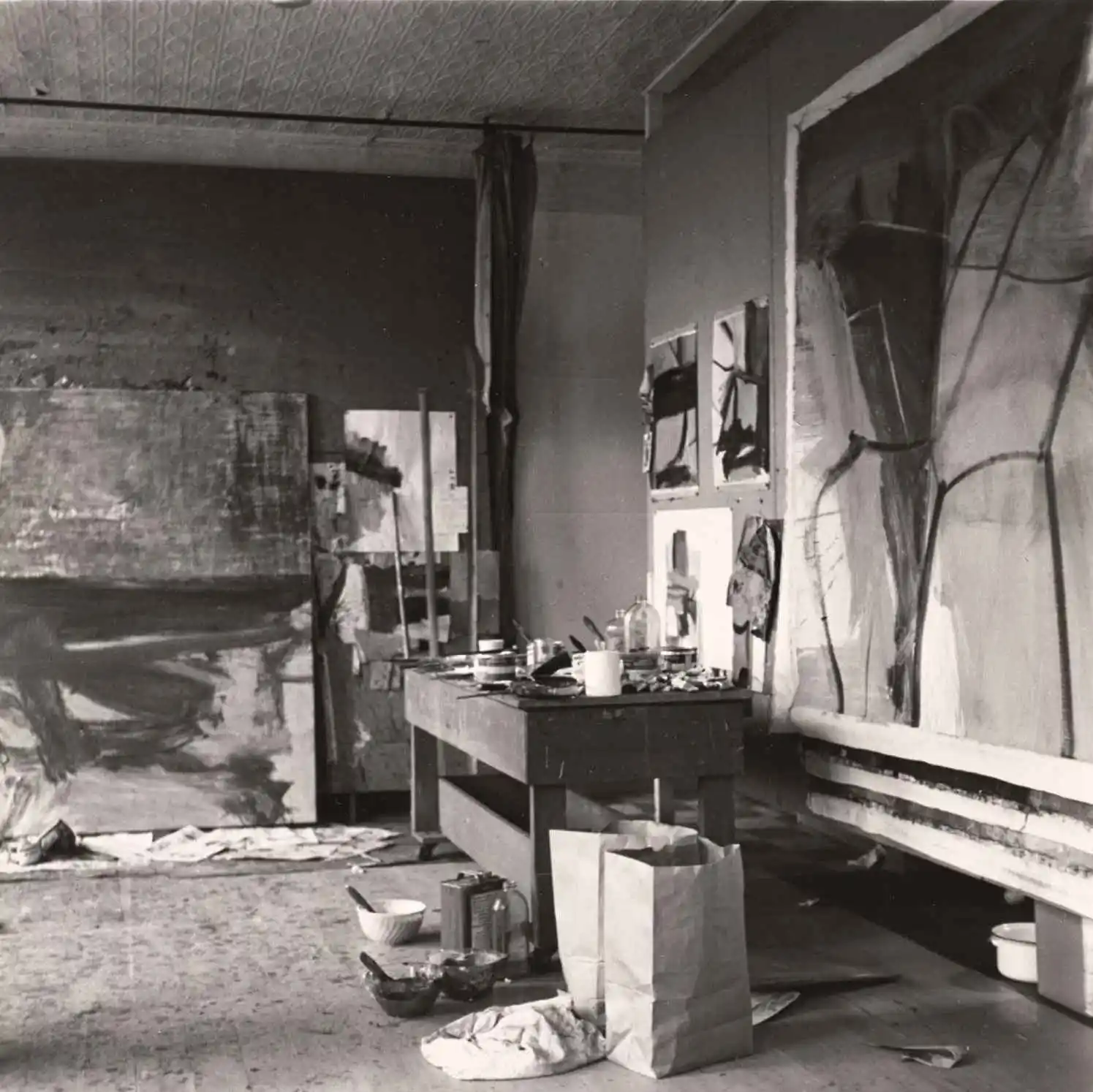

Walter Silver, Willem de Kooning's 10th Street Studio (1950) New York Public Library.

de Kooning traveled to Rome again and stayed with Kligman from July 28, 1959 until January of 1960. He rented a place at the Pensione Pierina, 47 Via Due Macelli; Kligman stayed at the Excelsior Hotel. He was popular with Roman society and was entertained by Dado Ruspoli, the son of the prince of Ruspoli. He began working on a number of paintings using black enamel mixed with ground pumice and also created a number of collages. And although Sidney Janis came to preserve his work for the Friends, he gave it out recklessly upon her departure.

In September, 1959, Ward took de Kooning’s child and moved to San Francisco. Despite his journey there to persuade her to return to New York, she remained on the west coast. From December 16, 1959 to February 17, 1960, the Museum of Modern Art showed some of de Kooning’s work in the exhibition Sixteen Americans.

In early 1960, Michael Sonnabend and Robert Snyder filmed a documentary entitled Sketchbook No. 1: Three Americans, which featured de Kooning. de Kooning, by Harriet Janis and Rudy Blesh, was published by the Grove Press. de Kooning became weary of the parties and the phone calls and upon his return from Italy hired a young artist named Dane Dixon to act as his assistant and his guardian during his bouts of drunkenness. Dixon also handled phone calls and assisted with carpentry projects.

That summer was spent in South Hampton; and in late 1960, he went to San Francisco for a month to visit Ward and his child. While there, he did lithographs in Berkeley and visited local galleries with a New York acquaintance, Nathan Oliveira. Characteristically, de Kooning’s drinking escalated. While intoxicated, he demanded that Ward return to New York with him, bringing their child, or he would sever all contact. Ward reluctantly agreed, and they stayed in his Broadway studio while he located and renovated an apartment for them.

His alcoholism accelerated throughout the ‘60s, and de Kooning wandered the streets in a state of disrepair, often mistaken for homeless. But in 1961, he purchased more land in the Springs. Near the end of that year, he had yet another affair with Marina Ospina, who was recently separated from her abusive husband.

1962 was another important year for de Kooning. Along with his usual escapades of affairs and exhibitions, this was the year he became a United States citizen. His March 1962 exhibition at the Sidney Janis Friends was unsuccessful, but that same month, he began seeing yet another woman, Mera McAlister. McAlister was of mixed-race heritage, a gospel singer and reportedly promiscuous. Their relationship lasted into the winter, and it was McAlister’s young son who coined the term “ice cream colors” in reference to de Kooning’s paintings, a term which de Kooning himself used later in an interview for Harper’smagazine.

Sidney Janis allowed Allan Stone to sell some of de Kooning’s smaller pieces in the autumn Sof 1962, and on October 23, Newman-de Kooning, an exhibition of “two founding fathers” opened at the Allan Stone Friends, which was located at 48 East 86th Street. The pairing worked well, as Barnett Newman’s drawings were frequently similar to the drawings of de Kooning, and the association with de Kooning in a mutual exhibition brought Newman favorable press.

Meanwhile, Sidney Janis Friends held The New Realists group show from October 31 – December 1, 1962. The after-opening gathering at the home of Burton and Emily Tremaine, included such names as Andy Warhol, Bob Indiana, Roy Lichtenstein, and Tom Wesselmann. Picassos hung next to de Koonings in the Tremaine residence. de Kooning himself, however, was politely asked to leave when he arrived uninvited, which he did without protest. That winter, Elaine painted President Kennedy’s portrait for the Harry S. Truman Library.

de Kooning was losing his battle with alcoholism. In March of 1963, he moved back to the Springs to live with Joan Ward and his daughter. Elaine had ceased painting upon receiving the news of President Kennedy’s assassination. By summer, he had moved to East Hampton, Long Island, and it was there that he painted Clam Diggers. He was harboring bitterness toward the new “pop art” movement.

By the end of the summer, de Kooning had begun an affair with his neighbor, Susan Brockman, moving in with her and her friend Clare Hooten. At the end of the rental of the vacation home, he and Brockman moved to a summer cottage on Barnes Landing, and then to a house owned by Joan Ward’s friend and fellow painter, Bernice D’Vorazon. After being evicted by D’Vorazon, the couple stayed briefly with Frederick Kiesler, who was renting John and Rae Ferren’s home on Springs Fireplace Road. The volatile nature of their relationship (i.e. broken items and busted walls) resulted in Ferren also asking the two to leave.

In the winter of 1963, de Kooning and Brockman moved the remaining possessions from 831 Broadway to Long Island. His alcoholism progressed, and he was hospitalized at one point. His sobriety, however, was short-lived, and that winter he produced only one painting, Two Standing Women. In about the spring of 1964, de Kooning and Brockman rented a house from Nicholas and Adele Carone, spending a year on Three Mile Harbour Road near his studio on Woodbine Drive.

Plans for a retrospective with Eduard de Wilde of the Stedelijk Museum in Holland were underway in 1964, with a target opening date in 1968. Meanwhile, Joan Ward and Lisa returned to New York City, residing in a 3rd Avenue apartment where they stayed for three years. They kept in close contact with de Kooning, who commuted from the Springs where he was renovating his studio. When the six doors he had ordered neither fit nor were returnable, de Kooning simply used them as canvases.

Willem de Kooning in his studio (1961) Smithsonian Institution Archives. Washington, DC

The Presidential Medal of Freedom, a distinguished honor, was awarded de Kooning in September 14, 1964. While other guests arrived at the White House in limousines for the ceremony, de Kooning arrived on foot, much to the amusement of the White House guard. de Kooning established a friendship with Joseph Hirshhorn, a conniving art collector, mistaking him for a loyal patron and doing considerable business with him. The September issue of Vogue magazine featured Harold Rosenberg’s profile of Willem de Kooning.

The Decisive Years, 1943 to 1953 exhibited at the Institute of Contemporary Art from January 13 – February 19, 1965, including work by Barnett Newman, Jackson Pollock, Clyfford Still, and Willem de Kooning. In February, de Kooning officially severed his association with Sidney Janis, resulting in multiple suits and counter suits. de Kooning continued exhibiting, accepting a retrospective at Smith College from April 8 – May 2, was a small retrospective of thirty-five paintings.

That spring, de Kooning and Brockman moved into a rented cottage, and on a bender separated in the summer of 1965, reuniting the following winter. That fall, he drew up a will leaving most of his money to daughter Lisa and giving paintings to Joan and Lisa. At this point, he was attempting to divorce Elaine, even giving her an entire collection of drawings, but the divorce was never finalized.

John McMahon had been working as de Kooning’s personal assistant for twelve years, and in 1965, his status became part time so Michael Wright was hired to help. de Kooning spent much of his time in drunken stupors, ranting of his hatred for both his mother and Elaine, and his alcoholism had begun to cause frequent and regular hospitalizations. About this time, he entered into an affair with Molly Barnes, whose family was in the movie industry. On October 13, his Police Gazette sold for $37,000.

de Kooning was admitted to Southampton Hospital in January of 1966, the result of a severe binge; however, he was released in time to attend Lisa’s birthday party in New York. Afterward he returned to Long Island alone. He aligned himself with anti-war protests, grew his hair, and began drawing a new series of American girls, including Women Singing I, Women Singing II, and Screaming Girls.

de Kooning’s Success and Fame Increase, 1967-1985

By 1967, de Kooning was achieving great success and notoriety, accompanied by much pressure due to his need to produce, coupled with his increasing alcoholism and personal chaos. Walker and Company published 24 of his charcoal drawings. He also joined the prestigious New York Friends, M. Knoedler and Company, in establishing a contemporary art department. A contract negotiated by Lee Eastman guaranteed de Kooning a $100,000 annual fee, giving the Friends first-refusal rights for his work. This inspired him to produce paintings with gusto, and on August 4, he presented 22 paintings in addition to the original 17 he had provided them. Included in the collection were several of the Women on the Sign works.

Joan Ward brought Lisa to live with de Kooning in the Springs that year, and de Kooning devoted himself to drawing. M. Knoedler and Company opened his first exhibition on November 10, showing Woman Sag Harbour, Woman Accobana, Woman Springs, and Woman, Montauk, along with other works. de Kooning declined attendance at the opening and other parties, and the exhibition met with mostly negative reviews, even though there were some sales. In typical fashion, he dealt with the rejection with increased alcohol abuse and was in Southampton Hospital by the end of the year.

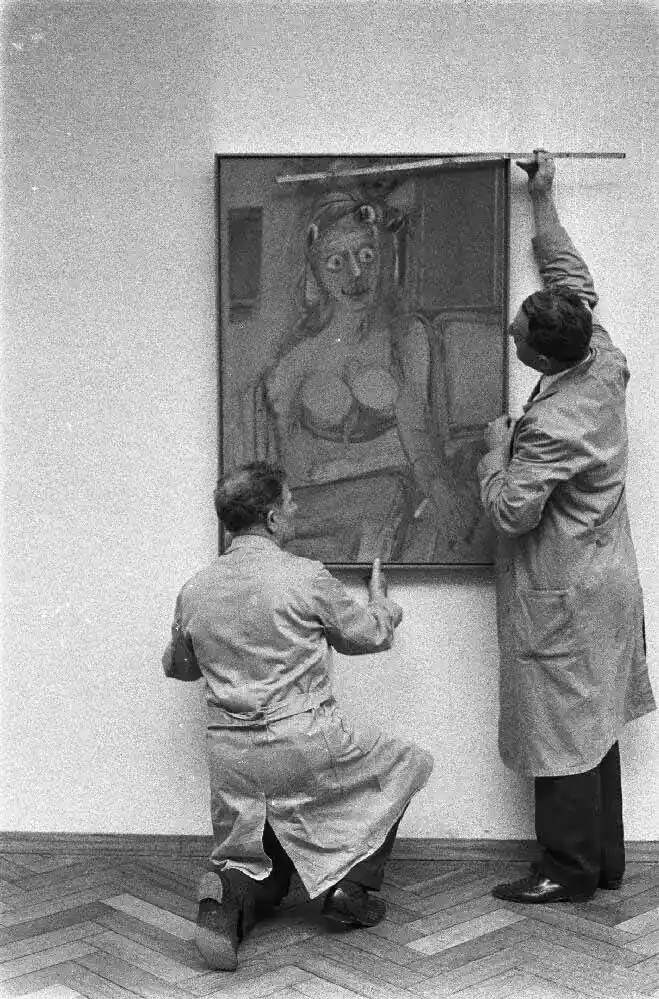

In 1968, de Kooning traveled to Europe, accompanied by Ward and Lisa and his friend Leo Cohan. He made the journey to Holland, his birthplace, for a major retrospective which opened September 18 at Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. Although he attended the show, his anxiety caused him to leave quickly, accompanied by his sister Marie and his step-brother, Koos Lassoy. On September 19, they visited their mother, who was by then quite fragile. His mother would later die on October 8. de Kooning drank heavily that Thanksgiving, and he and Ward were involved in a car crash, which they survived.

That summer de Kooning went to Italy, taking Susan Brockman with him; of course, Ward was not happy with the arrangement. Upon his return, he stayed with Brockman and visited Ward and Lisa. He also began sculpting and hired David Christian to build a large experimental version of one of his smaller works, Seated Woman.

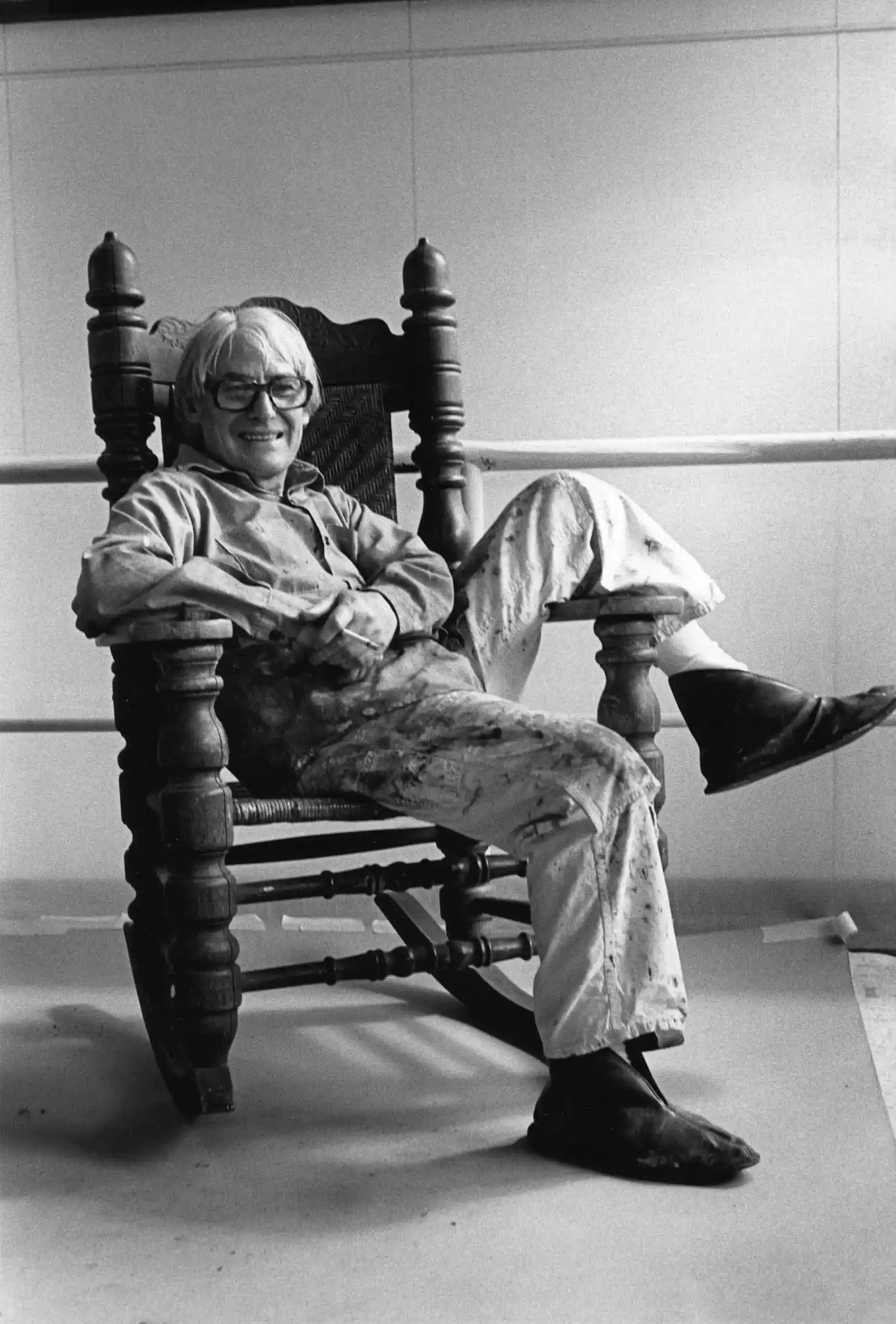

Willem de Kooning (1975), Photography, East Hampton, New York.

de Kooning traveled to Japan in 1970. After returning, he began working in lithography that summer, producing Love to Wakakoand Weekend at Mr. and Mrs. Krishner. In August, he began an affair with Emilie (Mimi) Kilgore. This, of course, was disturbing to both Ward and Mimi’s husband, John Kilgore, but de Kooning declared that he was in love.

de Kooning began painting his “Woman” compositions in 1950, which proved to be a major year for the artist. Excavation was painted in the spring, and in June, he began Woman I, possibly his most famous work. Although this was not his first Woman picture, having done a similar piece in 1944 and one in 1948, this painting was unique due to its enormity, standing nearly seven feet. Additionally, the portrayal was disturbing to most viewers, and de Kooning remarked that he was painting the irritation he often felt toward women, as opposed to their beauty.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s selection jury was notoriously hostile toward the artists of the abstract movement, so Robert Motherwell and Ad Reinhardt at Studio 35 attempted to form a group, calling themselves Abstract-Expressionist, Abstract-Symbolist, or Abstract-Objectionist. Ultimately the naming of a group was rejected in favor of writing a letter to The New York Times, in which the artists publicly objected to the national jury of selection. The group, supported by Jackson Pollock, picketed the museum and refused to submit art. The New York Herald Tribune called the group “The Irascible Eighteen,” attacking them for distorting facts. The protest received coverage from Time, Life, Art Digest, Art News, The Nation, and other magazines, and on November 26, Life magazine photographed the group, including Pollock who came from Manhattan for the shoot.

de Kooning was one of six artists chosen by Alfred Barr in 1950 to participate in an exhibition of young American painters in the U.S. Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Meanwhile, Sidney Janis Friends held an exhibition called Young Painters in the U.S. and France. The exhibition, which Janis worked on with Leo Castelli, paired American artists with French ones. de Kooning’s Woman(1949-50) was paired with Jean Dude Kooning’s L’Homme au chapeau bleu (1950).

In 1951, Excavation was exhibited in Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America in the Museum of Modern Art from January 23 – March 25. The show was categorized as “pure geometric,” “naturalist geometric,” and “expressionist biomorphic.” In February, de Kooning appeared at a symposium organized by the Museum of Modern Art, explaining his interpretation of abstract art.

In April 1951, de Kooning enjoyed another one-man show, again at the Egan Friends. The earnings were disappointing, however, as the limited sales (three drawings and two paintings) went to absorb the expenses of the exhibition. Despite increased publicity and acclaim, this was a financially poor year for de Kooning. Charles Egan had married Betsy Duhrssen in 1948, while having an affair with Elaine; and in 1950, Durhssen’s mother purchased Light in August for $750 from Egan’s Friends as a gift for the couple. These proceeds were also absorbed, and de Kooning received no money from the sale.

That year, the historic artist-organized Ninth Street Show was held at 60 East 9th Street, including the work of Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, Hans Hofmann, and James Brooks, along with de Kooning’s Woman. Sidney Janis began supporting de Kooning financially in the spring of 1951, advancing him money for art supplies on the condition that he change the name of his studio to the Janis Friends. The name change became official in 1953.

Excavation won a $4,000 first prize in the 60th Annual American Exhibition: Paint and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago in the autumn of 1951. de Kooning was one of 20 artists chosen for the American Vanguard Art for Paris Exhibition at the Sidney Janis Friends December 26, 1951 – January 5, 1952.

After much effort in January and February of 1952, de Kooning ceased work on Woman I, giving up on it until art historian and friend, Meyer Schapiro, encouraged him to revisit it in June. He renewed his efforts and pronounced it finished in mid-June 1952, only to begin more revisions in December. During this time, he also created several new “Woman” pictures.

Although Willem and Elaine were technically separated, he living in his studio and she in an apartment on Carmine Street, Elaine accompanied him to the Hamptons in the summer of 1952. They stayed with Leo Castelli and Ileana Sonnabend at their home on Jericho Road. Regular visitors were art critic Harold Rosenberg, who lived nearby, and Jackson Pollock.

Reclining Figure (1969), Sculpture, Rotterdam.

de Kooning moved to 88 East 10th Street in the autumn of 1952, spending much of his time with Harold Rosenberg. He met Joan Ward, a student at the Arts Students League, who was living in the Artists’ Building on 10th Street. Ward had a fondness for de Kooning and spent increasing amounts of time at his studio, sharing his whiskey and eventually becoming pregnant with his child. The pregnancy was aborted.

In 1953, de Kooning officially changed the name of his studio to the Janis Friends. His first show at the Sidney Janis Friends opened in March 1953. A small retrospective of his work was held at the Workshop Center for the Arts in Washington and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

In 1953, art student, Robert Rauschenberg, undertook an artistic experiment in which he, over a period of three weeks, erased one of de Kooning’s drawings with his permission. Under the impression that it was a private experiment, de Kooning was enraged to learn it was exhibited as Erased de Kooning.

Still, he was able to participate in Venice Biennale with Excavation in 1954, which propelled him into fame as a leading Abstract Expressionism artist. That summer he rented a Victorian house in Bridgehampton with Elaine, which they shared with Nancy Ward, Ludwig Sander, and Franz Kline. Although the troop was reportedly quite poor, they managed as steady supply of alcohol and attracted many visitors. de Kooning was able to make some sales to Martha Jackson and used the money for fare for his mother to visit. Her criticism was constant, and their verbal attacks led to her staying at the home of Martha Bourdrez, a Dutch artist and friend of de Kooning. During this time, de Kooning began to paint abstract urban landscapes, working in bright colors that he referred to as “circus colors”.

In 1955, Joan Ward became pregnant with de Kooning’s baby, and on January 29, 1956, she gave birth to Johanna Lisbeth de Kooning. On April 3, his second one-man show at the Sidney Janis Friends was held, and this one was a complete sell-out.

de Kooning was staying with Ward and their daughter at Martha’s Vineyard when Pollock and Edith Metzger died in a car crash on August 11, 1956. Elaine returned from Europe two days later and joined them for the funeral.

In the autumn of 1957, de Kooning began an affair with Jackson Pollock’s former lover, Ruth Kligman, who had survived the crash that killed Pollock and Metzger. Later that year, de Kooning also indulged in a two-week liaison with actress Shirley Stoler, allegedly offering her a painting, which she declined. He was painting very little during this time.

In February of 1958, de Kooning took Ruth Kligman to Cuba to visit Ernest Hemingway’s house. Joan Ward, the mother of de Kooning’s daughter, was furious that he left without notice. Kligman and de Kooning drifted apart that spring, but reconciled in the summer and were together in Martha’s Vineyard. Here, de Kooning became acquainted with lawyer, Lee Eastman.

de Kooning moved his studio to 831 Broadway in early 1959, a large space with windows and a skylight. Thomas B. Hess wrote a monograph on Willem de Kooning, which was published by Braziller in New York. Sidney Janis Friends held a May 4 exhibition of the large abstractions de Kooning was currently producing, a sell-out which included 22 oils bringing from $2,200 for a small piece to $14,000 for five large paintings.

The New American Painting as Shown in Eight European Countries 1958-1959 exhibition, held May 28-September 8 at the Museum of Modern Art, showed de Kooning’s Woman series, as well as some of his urban landscapes. On June 23, he bought 4.2 acres of land located on Woodbine Road, just off the main highway to East Hampton in the Springs of Long Island. The price was $500 an acre.

de Kooning traveled to Rome again and stayed with Kligman from July 28, 1959 until January of 1960. He rented a place at the Pensione Pierina, 47 Via Due Macelli; Kligman stayed at the Excelsior Hotel. He was popular with Roman society and was entertained by Dado Ruspoli, the son of the prince of Ruspoli. He began working on a number of paintings using black enamel mixed with ground pumice and also created a number of collages. And although Sidney Janis came to preserve his work for the Friends, he gave it out recklessly upon her departure.

In September, 1959, Ward took de Kooning’s child and moved to San Francisco. Despite his journey there to persuade her to return to New York, she remained on the west coast. From December 16, 1959 to February 17, 1960, the Museum of Modern Art showed some of de Kooning’s work in the exhibition Sixteen Americans.

Seated Woman (1969), Sculpture, Rotterdam.

In early 1960, Michael Sonnabend and Robert Snyder filmed a documentary entitled Sketchbook No. 1: Three Americans, which featured de Kooning. de Kooning, by Harriet Janis and Rudy Blesh, was published by the Grove Press. de Kooning became weary of the parties and the phone calls and upon his return from Italy hired a young artist named Dane Dixon to act as his assistant and his guardian during his bouts of drunkenness. Dixon also handled phone calls and assisted with carpentry projects.

That summer was spent in South Hampton; and in late 1960, he went to San Francisco for a month to visit Ward and his child. While there, he did lithographs in Berkeley and visited local galleries with a New York acquaintance, Nathan Oliveira. Characteristically, de Kooning’s drinking escalated. While intoxicated, he demanded that Ward return to New York with him, bringing their child, or he would sever all contact. Ward reluctantly agreed, and they stayed in his Broadway studio while he located and renovated an apartment for them.

His alcoholism accelerated throughout the ‘60s, and de Kooning wandered the streets in a state of disrepair, often mistaken for homeless. But in 1961, he purchased more land in the Springs. Near the end of that year, he had yet another affair with Marina Ospina, who was recently separated from her abusive husband. 1962 was another important year for de Kooning. Along with his usual escapades of affairs and exhibitions, this was the year he became a United States citizen. His March 1962 exhibition at the Sidney Janis Friends was unsuccessful, but that same month, he began seeing yet another woman, Mera McAlister. McAlister was of mixed-race heritage, a gospel singer and reportedly promiscuous. Their relationship lasted into the winter, and it was McAlister’s young son who coined the term “ice cream colors” in reference to de Kooning’s paintings, a term which de Kooning himself used later in an interview for Harper’smagazine.

Sidney Janis allowed Allan Stone to sell some of de Kooning’s smaller pieces in the autumn Sof 1962, and on October 23, Newman-de Kooning, an exhibition of “two founding fathers” opened at the Allan Stone Friends, which was located at 48 East 86th Street. The pairing worked well, as Barnett Newman’s drawings were frequently similar to the drawings of de Kooning, and the association with de Kooning in a mutual exhibition brought Newman favorable press.

Meanwhile, Sidney Janis Friends held The New Realists group show from October 31 – December 1, 1962. The after-opening gathering at the home of Burton and Emily Tremaine, included such names as Andy Warhol, Bob Indiana, Roy Lichtenstein, and Tom Wesselmann. Picassos hung next to de Koonings in the Tremaine residence. de Kooning himself, however, was politely asked to leave when he arrived uninvited, which he did without protest. That winter, Elaine painted President Kennedy’s portrait for the Harry S. Truman Library.

de Kooning was losing his battle with alcoholism. In March of 1963, he moved back to the Springs to live with Joan Ward and his daughter. Elaine had ceased painting upon receiving the news of President Kennedy’s assassination. By summer, he had moved to East Hampton, Long Island, and it was there that he painted Clam Diggers. He was harboring bitterness toward the new “pop art” movement.

Standing Figure (1969), Sculpture, Rotterdam.

By the end of the summer, de Kooning had begun an affair with his neighbor, Susan Brockman, moving in with her and her friend Clare Hooten. At the end of the rental of the vacation home, he and Brockman moved to a summer cottage on Barnes Landing, and then to a house owned by Joan Ward’s friend and fellow painter, Bernice D’Vorazon. After being evicted by D’Vorazon, the couple stayed briefly with Frederick Kiesler, who was renting John and Rae Ferren’s home on Springs Fireplace Road. The volatile nature of their relationship (i.e. broken items and busted walls) resulted in Ferren also asking the two to leave.

In the winter of 1963, de Kooning and Brockman moved the remaining possessions from 831 Broadway to Long Island. His alcoholism progressed, and he was hospitalized at one point. His sobriety, however, was short-lived, and that winter he produced only one painting, Two Standing Women. In about the spring of 1964, de Kooning and Brockman rented a house from Nicholas and Adele Carone, spending a year on Three Mile Harbour Road near his studio on Woodbine Drive.

Plans for a retrospective with Eduard de Wilde of the Stedelijk Museum in Holland were underway in 1964, with a target opening date in 1968. Meanwhile, Joan Ward and Lisa returned to New York City, residing in a 3rd Avenue apartment where they stayed for three years. They kept in close contact with de Kooning, who commuted from the Springs where he was renovating his studio. When the six doors he had ordered neither fit nor were returnable, de Kooning simply used them as canvases.

The Presidential Medal of Freedom, a distinguished honor, was awarded de Kooning in September 14, 1964. While other guests arrived at the White House in limousines for the ceremony, de Kooning arrived on foot, much to the amusement of the White House guard. de Kooning established a friendship with Joseph Hirshhorn, a conniving art collector, mistaking him for a loyal patron and doing considerable business with him. The September issue of Vogue magazine featured Harold Rosenberg’s profile of Willem de Kooning.

The Decisive Years, 1943 to 1953 exhibited at the Institute of Contemporary Art from January 13 – February 19, 1965, including work by Barnett Newman, Jackson Pollock, Clyfford Still, and Willem de Kooning. In February, de Kooning officially severed his association with Sidney Janis, resulting in multiple suits and counter suits. de Kooning continued exhibiting, accepting a retrospective at Smith College from April 8 – May 2, was a small retrospective of thirty-five paintings.

That spring, de Kooning and Brockman moved into a rented cottage, and on a bender separated in the summer of 1965, reuniting the following winter. That fall, he drew up a will leaving most of his money to daughter Lisa and giving paintings to Joan and Lisa. At this point, he was attempting to divorce Elaine, even giving her an entire collection of drawings, but the divorce was never finalized. John McMahon had been working as de Kooning’s personal assistant for twelve years, and in 1965, his status became part time so Michael Wright was hired to help. de Kooning spent much of his time in drunken stupors, ranting of his hatred for both his mother and Elaine, and his alcoholism had begun to cause frequent and regular hospitalizations. About this time, he entered into an affair with Molly Barnes, whose family was in the movie industry. On October 13, his Police Gazette sold for $37,000.

de Kooning was admitted to Southampton Hospital in January of 1966, the result of a severe binge; however, he was released in time to attend Lisa’s birthday party in New York. Afterward he returned to Long Island alone. He aligned himself with anti-war protests, grew his hair, and began drawing a new series of American girls, including Women Singing I, Women Singing II, and Screaming Girls.

de Kooning’s Success and Fame Increase, 1958-1997

de Kooning’s Final Years, 1985-1997

de Kooning produced 63 paintings in 1985. He was, however, beginning to show signs of Alzheimer’s and required help with menial tasks. Elaine changed his color palettes, and his assistants began mixing the tubes of paints. Among the paintings produced during this time were Untitled XIII and Untitled XX. His last show at Fourcade, Droll, Exhibition of de Kooning’s Recent Work from 1984-1985, was held in October.

In 1986, de Kooning completed 43 more works. The Anthony d’Offay Friends in London displayed Exhibition of Willem de Kooning’s Work From 1983-1986. The following year, he produced 26 paintings. Although his eyesight was failing, he continued to paint. By now, he was working from old sketches that his assistants projected onto blank canvases so that he could “fill in” areas.

Presentation of the Talens Prize to Willem de Kooning (1968), Photography, inv. 921-6939, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

That year, Pink Lady sold for $3.63 million. Xavier Fourcade , who had sold $9.3 million in the works of de Kooning, died of AIDS. The news was kept from de Kooning as Elaine thought it would upset him. Several years earlier, Elaine was diagnosed with lung cancer, and by 1987, her health worsened dramatically.

de Kooning produced another 27 paintings in 1988. Realizing the state of her health, Elaine encouraged de Kooning to change his will, making Lisa sole beneficiary. Due to the value of his work, Eastman blocked these attempts, threatening to make public de Kooning’s deteriorating mental state. The matter was dropped, and Eastman remained executor. Later that year, Elaine was admitted to Sloan-Kettering for an unsuccessful round of radiation treatment. On February 1, 1989, Elaine died at the age of 70. de Kooning was never told of her death.

Lisa de Kooning and Lee Eastman filed a court petition, declaring de Kooning mentally incompetent and incapable of managing his affairs. Eastman attempted to become sole conservator of the estate, and he alleged that Lisa had mismanaged her father’s money. His appeal was rejected by the courts, and the two became co-conservators. In May, de Kooning entered Southampton Hospital for a hernia operation; in July, he underwent prostate surgery.

Willem de Kooning stopped painting in 1990. A mini-retrospective, Willem de Kooning: An Exhibition of Paintings, was held at the Salander O’Reilly Galleries from September – October. de Kooning/Dude Kooning: The Woman exhibition at the Pace Friends ran from December 1990 through January 1991.

In May 1993, Jennifer McLaughlin, de Kooning’s final assistant left. October 21, Willem de Kooning from the Hirshhorn Museum Collection opened at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. Willem de Kooning: Paintings was exhibited at the National Friends of Art in Washington from May – September 5, 1994. And in 1996, the Rotterdam Academy, where de Kooning had studied as a young man, officially changed its name to The Willem de Kooning Academy. On March 19, 1997, at the age of 92, Willem de Kooning died. Some 300 people attended the funeral, including Ruth Kligman, Susan Brockman, Molly Barnes, and Emilie Kilgore. His daughter, Lisa, was the guest speaker.